🎵 Under the sea! 🦀

Is the subsea engineering sector adapting to the energy transition?

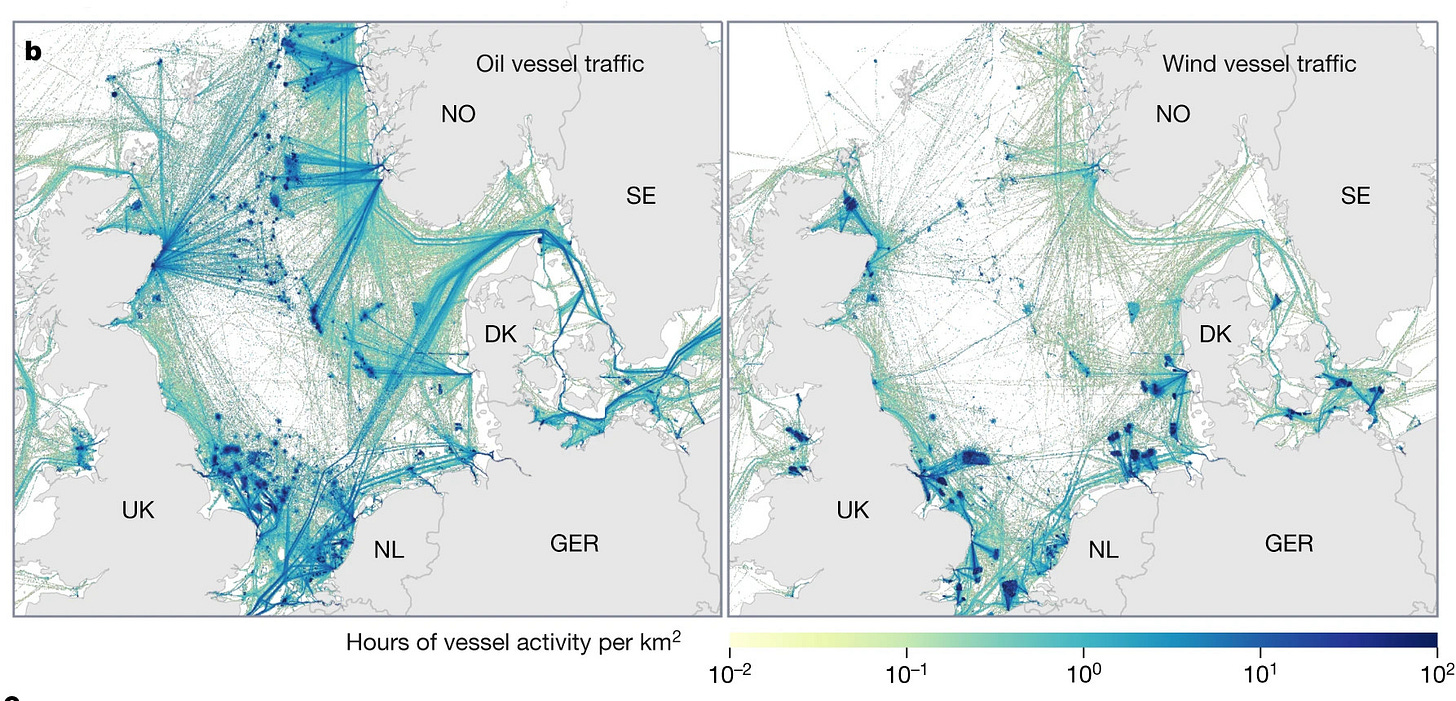

A recent quote from David Kroodsma, Global Fishing Watch’s head of research (via my business partner Sam, Adam Tooze and the FT) has stuck with me. Talking about his organisation’s latest research paper — an analysis of the previously unmapped activity of sea vessels and offshore infrastructure — Kroodsma points out that “the ocean economy is growing faster than the global economy”. GFW’s task is to use new technology, primarily satellite imagery and machine learning models, to make sure that it’s properly monitored.

It’s a persuasive framing of a growing issue — but I think we can be more specific. Much of the most economically productive (and potentially environmentally destructive) activity covered by GFW’s analysis relates to activities that happen under the sea. In the world of offshore energy, including both traditional oil and gas and the troubled but vital wind industry, this is known as the subsea engineering sector, and it’s made up of a relatively small number of highly specialised companies, based for the most part in Europe but operating globally.

One such firm is Subsea7, domiciled in Luxembourg, listed on the Oslo Stock Exchange and headquartered in the south London suburb of Sutton, where it’s important enough to the local economy to feature on the signs at the railway station.

Like many other firms in the oil field services and equipment (OFSE) sector, Subsea7 has undergone a recent marketing glow-up, presenting itself as a leading firm in the energy transition, with a focus on technologies like carbon sequestration. Its real business, however, is in riding the final crest of the fossil fuel wave, helping oil and gas companies develop increasingly baroque frontier projects while sucking the last drops out of existing fields through the deployment of new and improved subsea solutions.

A typical example of its work is a recent contract award by Petrobras, Brazil’s state-owned oil company, which involves Subsea7 laying pipelines for the extraction of crude oil from the Mero 4 field, located in the Santos Basin, roughly 120 miles off the coast of Rio de Janeiro. In a landmark 2022 paper, researchers at the universities of Leeds, British Columbia and Syracuse in New York identified the Santos offshore work as one of 425 ‘carbon bomb’ projects projects that will each emit over a billion tonnes of CO2 over their lifetime and put the goals of the Paris Agreement in jeopardy.

Academic work will likely do little to dissuade Subsea7’s management, with the company already deeply enmeshed in oil and gas work in South America’s largest economy. Using the interactive map available via our subscription to LSEG Workspace, we can display the current (as of 18 January 2024) locations of all offshore production, support and supply vessels whose registered owner contains the phrase “Subsea 7”, showing at least five in or near Brazil. The point on the north-eastern coast represents the Seven Cruzeiro, a pipe-laying vessel which appears to be undergoing work at the massive Atlântico Sul shipyard near Recife, recently discussed in the FT as a major part of president Lula’s domestic economic plans.

Beyond the obvious environmental harms involved in producing ever-increasing quantities of oil and gas, Subsea7’s fleet of ships also represents a potential hazard. Unearthed, Greenpeace UK’s excellent investigative journalism arm, recently tracked the final resting places of decommissioned vessels, searching specifically for those which end up in shipyards with poor safety standards in South Asia (for more on the issue, see Sam’s post from last year).

When Greenpeace analysed data from NGO Shipbreaking Platform, a campaign group which works specifically on this issue, they found Subsea7 to be one of the worst-offending UK companies, with three of its ships having been scrapped at Alang in India between 2018 and 2022. The company responded: “Subsea7 aims to operate a vessel for its entire useful life, investing in new equipment and enhancements to extend its life where possible. When a vessel reaches the end of life, we are committed to recycling it responsibly.”

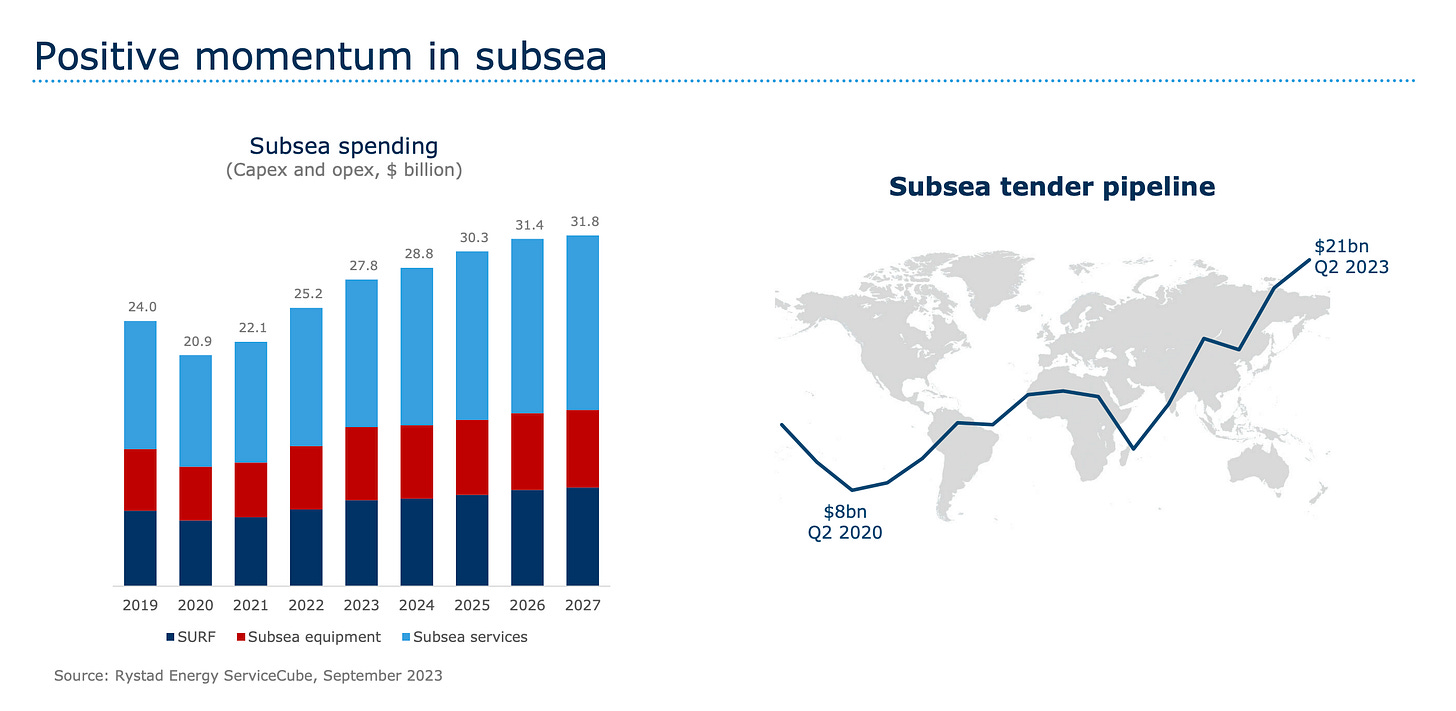

Whichever way you look at it, subsea engineering expertise will be crucial for the next phase of the energy transition. If carbon capture technologies continue their somewhat dismal record, companies and governments may struggle to adequately utilise ambitious offshore carbon sequestration projects, but deployment of offshore wind will continue to advance. The spectacular growth of solar in recent years also implies a need for more high-voltage interconnector cables to transmit power between geographies — a great example being the Xlinks project, which aims to bring solar power all the way from Morocco to the UK via a dedicated cable. And for decades to come there will be significant work to do in decommissioning our current system of fossil fuel energy infrastructure.

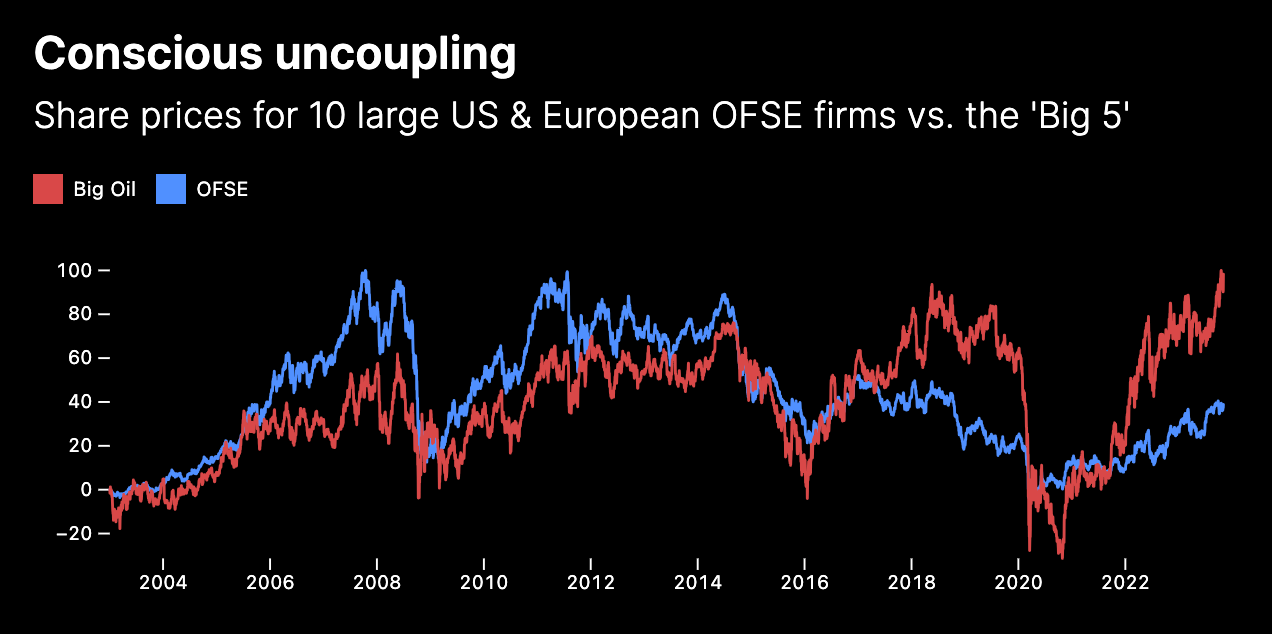

Companies like Subsea7 may seem lucky, then — for the time being, they enjoy a highly lucrative niche serving the world’s remaining fossil fuel projects, with the prospect of being paid again to clean it all up in the decades to come. All this while branding themselves as pioneers of the energy system of the future. But this isn’t how the market sees it. Our own analysis shows that, since the pandemic, companies in the broad OFSE sector have seen their share prices stagnate relative to the major integrated oil companies like Shell, ExxonMobil and Total, failing to benefit from resurgent international oil prices.

The message is clear, articulated at length in a 2021 report by McKinsey, the oil industry’s outsourced brain: OFSE firms must adapt or die. And there are signs that certain parts of the business model are easier to clean up than others. In 2021, engineering giant TechnipFMC hived off its Paris-headquartered, surface-focussed unit into Technip Energies, leaving the oily realities of the subsea work to continue from Houston, Texas. The French company now benefits from significantly more transition-centric branding and a less carbon-intensive project pipeline. (Not that this has helped its broader ESG image!) Other firms have formed subsea joint ventures, perhaps with similar intentions to insulate the rest of their businesses from the reputational and financial risks of frontier oil and gas development.

But for the energy transition to work, we need decarbonisation not just of the ‘easy bits’ of the industry, like sticking carbon capture on surface facilities, but of the hard work of building and operating infrastructure in the extreme environment of the seabed. Whether businesses with a purely subsea focus are up to the challenge will be reflected in their share prices — in the case of Subsea7, up since the pandemic, but still well below levels seen in the early 2010s. Subsea7 shareholders with strong sustainability credentials, like Sweden’s Storebrand Group, may wish to look closely at the company’s business plans going forward.