How we investigated a carbon capture flop

... and how you can too using EPA and state-level company filings

Earlier this week, Natasha White and Akshat Rathi wrote an excellent article in Bloomberg on Occidental and its plans to dominate the US carbon capture market.

Data Desk's analysis was used to show that there are reasons to be very cautious about some of the more bombastic claims made by companies like Occidental concerning the potential for carbon capture and storage (CCS) to reduce global warming.

Occidental’s CEO, Vicky Hollub, has gone out on a limb amongst other oil executives by committing the company to “net-zero” direct and indirect emissions by 2050. How on earth can you produce “carbon-neutral” oil, one might reasonably ask? Well, Occidental’s view is that through a process known as enhanced oil recovery (EOR), you can permanently sequester CO2 captured from the atmosphere so as to offset the emissions of the oil when it is eventually burned.

This is why Occidental is betting big on carbon capture and building a billion-dollar project called Stratos to suck CO2 directly out of the atmosphere. Stratos is intended to be the first of many Occidental direct air capture plants, ultimately giving the company more CO2 to inject into its depleted oil wells to flush out the remaining hydrocarbons. If the concept of “net-zero oil” sounds a little too mind-bending, there is a great interview with Vicky Hollub by Akshat Rathi on his Bloomberg Zero podcast, where these issues are discussed further.

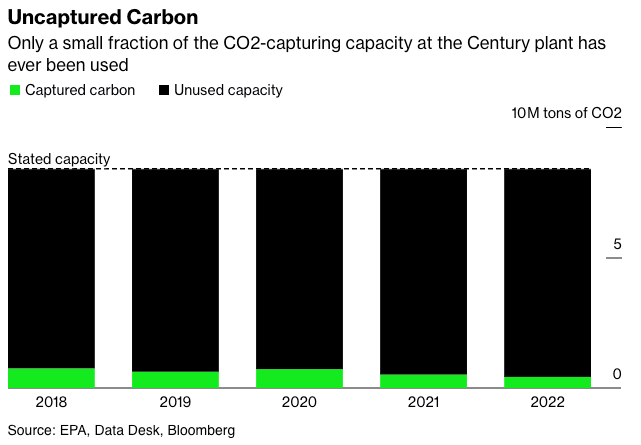

What CCS boosters like Hollub often paper over is carbon capture’s track record of failure, including Occidental’s much-vaunted past projects. Our analysis of Occidental's Century Plant — once the world's largest CCS facility by nameplate capacity — shows that it fell well short of its promise.

Will the next generation of CCS facilities — including direct air capture projects like Stratos — beat this losing streak? Or will CCS continue to be an underperforming distraction pedalled by fossil fuel companies to keep their business model alive?

Read more over on Bloomberg Green.

The 🤓 bit (data journos read on)

In the course of producing the analysis for Bloomberg, we reviewed several public data sources for investigating facility-level carbon capture rates and the quantities of CO2 injected at various sites.

This information is surprisingly difficult to come by when you consider the size of subsidies on offer for the sequestration of anthropogenic CO2 in the Inflation Reduction Act, which the US Treasury estimates will cost $2.3 billion between 2020 and 2029.

Two years ago, the IRS stopped publishing figures on how many credits are claimed under the 45Q tax credit scheme. The main source of information on CO2 suppliers and injectors comes from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), where you can access companies' facility-level greenhouse gas reports.

However, these don't tend to give you a very good picture of who is capturing what and where the CO2 is being injected. For reasons of commercial confidentiality, the relevant bits of Subpart PP (for CO2 producers) and Subpart UU (for CO2 injectors) are redacted.

You can get some information on companies that choose to file as part of Subpart RR on what they inject, but many companies opt out of this, choosing to verify the amounts of CO2 sequestered — and available for tax crediting — via a separate mechanism. The EPA publishes some aggregate statistics annually on CCS, but more creative approaches are required for data journalists and analysts who want to dig a little deeper into specific facilities.

It is possible to estimate the amount of CO2 available to capture for some CCS plants by using figures derived from their EPA greenhouse gas filings. For gas processing plants like Century, which use acid gas removal technologies that strip CO2 from sour gas, you can estimate the amount of CO2 available to capture using figures disclosed in Subpart W of their greenhouse gas filings. To do this, you use the amount of natural gas that enters the acid gas removal unit combined with the disclosed concentration of CO2 in the raw gas. This method gives an upper limit for what may have been captured.

There are also two lesser-known state-level datasets that can be used to assemble a picture of how much CO2 gas processing plants capture and where it is injected.

The Wyoming Oil and Gas Conservation Commission collects and publishes some of this information for facilities in Wyoming. The data portion of their site is written almost exclusively in Comic Sans, but don’t let that fool you. There is some seriously interesting stuff in there. You can get monthly data on Shute Creek — another giant CCS facility — including how much CO2 it vents, flares and sells. This is all published in their Form 9 filings, a list of which is available here.

The equivalent agency in Texas is called the Texas Railroad Commission. Given that much of the CO2 sequestered in the US is injected in the Permian Basin, this is potentially the richest source of data, and they publish large amounts of data via their “Research Queries” service. From our scouring, there are two highlights:

Form H10 reveals information at the well level about the quantities of CO2 that are being injected. The interesting thing about this is that companies sometimes disclose whether that CO2 is anthropogenic. The downside is that it appears to be voluntary as to whether a company makes the distinction between natural and anthropogenic CO2.

Form R3 for natural gas processing gives information on the quantities of CO2 and sulphur recovered.

Both the H10 and R3 forms are available for bulk download — always a good thing for the type of analysis Data Desk does. However, the bulk files are only made available in an outdated mainframe format that requires you to either use proprietary software or write your own parser (which we did).

Honourable mention also has to go Rextag, which has some excellent data on CO2 pipelines and other CCS-related infrastructure.

We will continue to dig into the US CCS industry over the coming months, so please contact us if you’re interested in collaborating.