Tracing the movements of dead tankers

In 2018 the European Union banned EU-flagged vessels from being recycled in dangerous ship-breaking yards, but this hasn’t stopped the practice for tankers that call at European ports

What happens to the great hulking vessels that haul the goods we use daily when they get old?

These seaborne beasts — tankers, bulkers and cargo ships — can’t be crushed and cubed in a scrapyard on the outskirts of your average town. Their size requires huge amounts of time, space and labour to take apart. In some cases, their hulls contain toxic and even radioactive materials, which are dangerous to the people who break them up and their surrounding environment.

This work is done mainly on South Asian beaches, and it is insanely hazardous for the labourers involved. About 70% of vessels end up in the ship-breaking yards of Alang in India, Chittagong in Bangladesh and Gadani in Pakistan. Low-paid migrant workers dismantle the ships inside and out, often with no safety or protective equipment. As a result, accidents and fatalities are common as workers put in long shifts cutting up the very structures that hold them tens of metres above the ground.

The NGO Shipbreaking Platform has been researching and campaigning for better oversight of the global shipbreaking industry for over 14 years. It has called out numerous ship-owning companies and operators for irresponsible scrapping practices. Their investigations have prompted a successful criminal prosecution setting a legal precedent in the EU.

Quite rightly, much campaigning has tended to focus on the companies most immediately involved and who often shirk responsibility: ship owners, scrap re-sellers and the ship-breaking yards themselves. This year Platform highlighted China’s role as a significant dumper on South Asian shores and fingers Berge Bulk as one of the worst corporate offenders, having scrapped four vessels in Bangladesh and India in the past four years.

Doubly offshore

Partly as a result of the campaigning of groups like Platform, the EU introduced rules that require EU-flagged vessels to be recycled only in approved ship-breaking yards where labour and environmental standards are upheld. But this hasn’t stopped vessels that service European ports and oil and gas fields from being broken down in problematic ship-breaking yards. After all, shipping companies that serve Europe can re-flag ships to non-EU jurisdictions when they’re approaching their end.

The practice of using “flags of convenience” — registering ships to lightly-regulated jurisdictions with little to no connection to the commercial activity of the vessel — is widespread. Liberia and Panama are two of the most popular flags.

Countries like St Kitts and Nevis, Comoros and Palau offer a more bespoke service. They provide flags that offer operators cheap deals on “last voyages” and tend to be particularly lax on the oversight of how ships are recycled.

Tracing tracks

Each year Platform releases a dataset of vessels broken up worldwide, enabling people to assess whether companies are behaving responsibly when it comes to the disposal of the ships they own. This dataset includes bulkers and tankers but also floating drilling and storage platforms, essential for the offshore oil and gas industry.

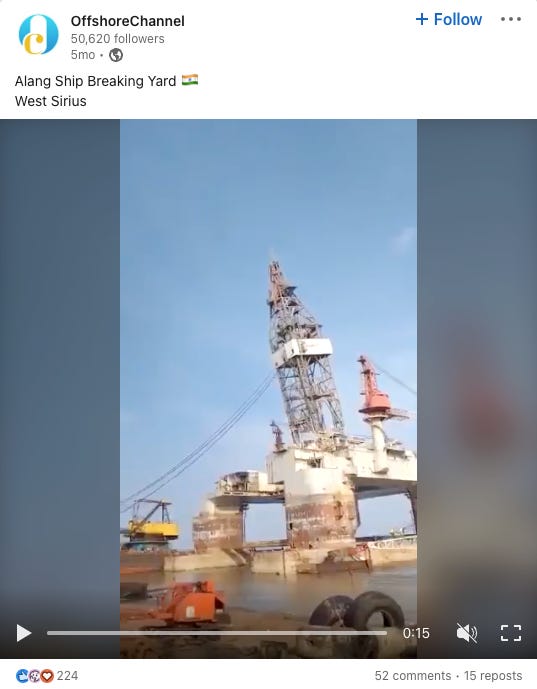

The West Sirius, for instance, a semi-submersible ultra-deepwater drilling rig, is marked in Platform’s dataset as having been scrapped at Alang, India — a notorious ship-breaking yard at which three deaths were reported in 2022 despite a downturn in scrapping volumes due to high freight rates. It spent most of its life in the Gulf of Mexico and, at one point, was assigned to BP for exploration work.

It made its final journey from the Coast of Texas to India, flying under a Panamanian flag last year. Its safety signal — something that enables us to track the location of vessels — disappeared after it reached Cape Town in South Africa. A LinkedIn post shows it being taken apart in Alang five months ago.

I took a closer look at the Platform database for 2022 published at the start of this month to see if we could enrich this data to find out more about the lifecycle of ships and the solutions to this necessary but highly dysfunctional industry.

I plotted the last ten year’s worth of tracks of all of the 292 vessels broken up at Chittagong (Bangladesh), Alang (India) and Adani (Pakistan) in 2022. These breaking yards have some of the world’s worst safety records.

Unsurprisingly the picture is global, with hotspots in Europe, the Middle East and the Pacific. The Netherlands, Spain and Italy are some of the most popular destinations these vessels visited to deliver their cargo. The Netherlands alone took delivery of 910 million barrels of crude from these vessels during this time.

Where will all the old stuff go?

The West Sirius won’t be the last drilling platform to be scrapped in controversial breaking yards. The offshore oil and gas industry will send vast amounts of infrastructure to the scrap heap in the coming decades, a process that will be accelerated by the energy transition. In the Asia-Pacific region alone, Wood Mackenzie estimates that 2,600 platforms and 35,000 wells will need to be decommissioned in the next decade.

As this process unfolds, it will be essential to recognise not just where the infrastructure is legally registered but where it operates and who it benefits. Only then will the cost of disposing of it responsibly be equitably distributed.

One solution put forward by Platform is to require ships visiting European ports to pay into a pot that could be reclaimed by the final owner when the vessel needs to be recycled. The money could only be accessed if an approved ship-breaking yard was used, providing a financial incentive for recycling ships responsibly.

Judging by what the vessels do during their life based on their tracks, there’s a lot to recommend this approach.