Scholz the cautious LNG shipper

The German government controls two ice-class tankers for shipping Russian LNG — what's it going to do with them?

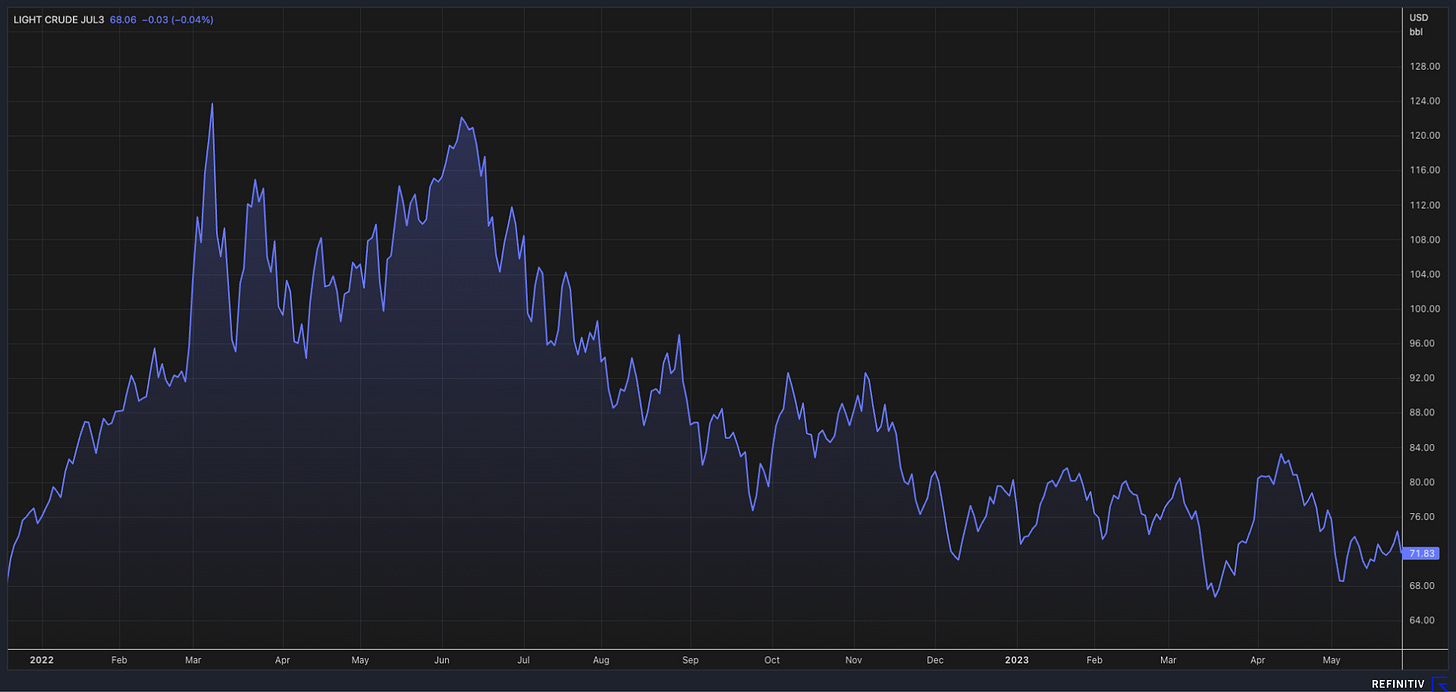

Much has been made of Joe Biden as a master crude trader. At the height of last year’s energy crisis, the US president decided to release millions of barrels of oil from his country’s Strategic Petroleum Reserve, a move which — given a precipitate fall in prices over the second half of 2022 — now looks pretty smart (although a meeting of OPEC+ this Sunday could bring a sting in the tail).

Wars do strange things to the global energy system, and Biden wasn’t the only world leader pushed into the trading business by the events of last year. In November, the German government nationalised Gazprom Germania, a subsidiary of the Russian state gas firm, creating the new entity Securing Energy for Europe (SEFE) GmbH. SEFE is now set up with a website and offices throughout the world, including a commercial gas supplier based in Manchester and a trading division in London.

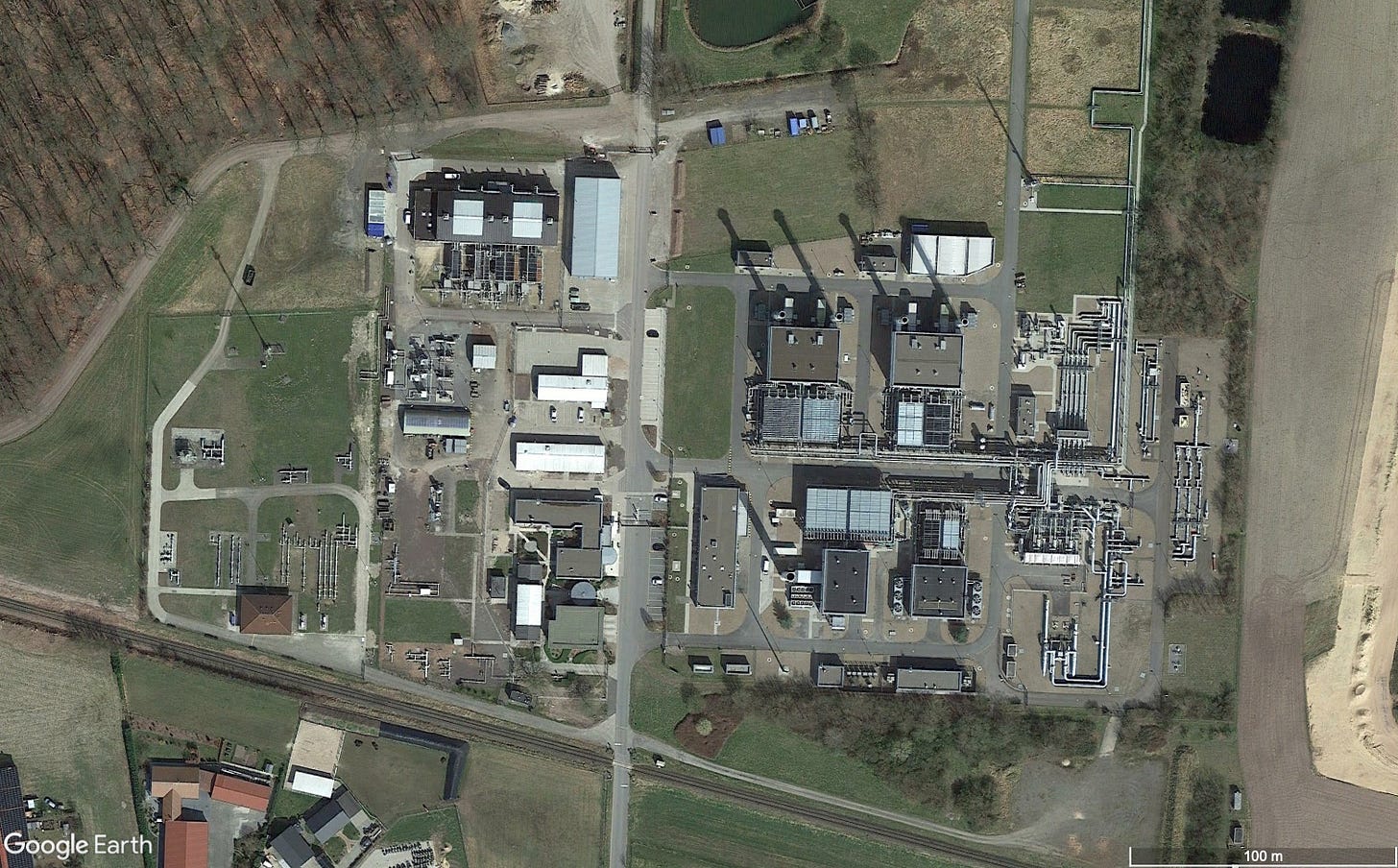

For most of Gazprom Germania’s physical assets, this move had an obvious logic: gas storage facilities and distribution pipelines are located in Germany. In fact, the German government began filling up the massive underground gas storage at Rehden as early as May last year, while Gazprom Germania was still being administered by the German regulator.

But what about things that move? Among the most interesting assets now controlled by the German government are three liquefied natural gas (LNG) tankers: the Amur River (IMO 9317999), the Ob River (9315692) and the Clean Energy (9323687). The first two of these* are ice-class vessels, designed for picking up cargoes exclusively from the chilly seas of northern Russia. At the time of writing, this means the Sakhalin-II terminal at Prigorodnoye and the Yamal LNG terminal at Sabetta, but Russia’s massive ambitions for LNG exports could see new projects — substantially enabled by European companies and technology — come online as early as this year.

While the ships are still owned by the Greek firm Dynagas, the German government has taken over a long-term charter agreement reportedly lasting until 2028, meaning that SEFE is free to do what it pleases with them for the next five years. As the SEFE website itself makes clear, these vessels’ ice-class status makes them “capable of transporting from any existing LNG terminal, as well as [able] to transit the Northern Sea Route [(NSR) — the Arctic corridor between Russia and China] if required.” Which raises an obvious question: will it, eventually, be required?

So far, the answer appears to be a firm “no”. In May last year, according to data from Refinitiv, both ships carried their last cargoes from Sakhalin-II to China and Japan, before sitting at anchor off Prigorodnoye for months, presumably casualties of diplomatic wrangling over how exactly to re-integrate them into the global fleet. They sprang back into life in late August and have so far picked up cargoes from the United States, United Arab Emirates, Cameroon, Egypt and Algeria, delivering them mostly to northern France and Gujarat, India.

Pootling around the Med and the Indian Ocean is a far cry from transiting the NSR, and SEFE’s decision to take these two tankers out of regular service may have helped exacerbate a spike in freight rates for deliveries from Yamal LNG last summer. The chart below shows the price for eastbound Yamal cargoes, which broke $2/MMBtu for deliveries to Taiwan in late August, right at the start of the annual two- to three-month period in which the Northern Sea Route becomes navigable by ice-class LNG tankers.

So, will the Ob River and Amur River ever ship Russian LNG again? While Russia has big plans to expand its own fleet of ice-class tankers — part of a broader strategic opening-up of the Northern Sea Route — international sanctions threaten to thwart these ambitions, or at least to delay progress significantly. Meanwhile, new sanctions on LNG — which has so far flown under the radar relative to US and European restrictions on Russian oil — loom large, with the EU planning a rule which would allow member states to ban the commodity from their infrastructure.

In a world where Europe no longer buys Russian LNG, the importance of routes to Asia only increases — and with more Russian production scheduled to come online, all signs point to a shortage of tankers and big rewards for anyone with an ice-class up their sleeve. Unlike Biden, the smart trade for Scholz may be to lose money.

* And potentially the third, according to SEFE’s own fleet list, although other sources disagree.