Van Oord dredges through coral reef for Mozambique gas pipeline

With the Mozambique LNG mega-project due to restart, we take a look at recent activity at the site using AIS data and satellite imagery

When the Italian oil giant Eni discovered a massive gas field off the coast of northern Mozambique in 2012, the company named it Coral, taking inspiration from the spectacular reefs surrounding the drilling site. More than a decade later, the next phase of oil and gas development offshore Mozambique threatens the species that gave it its name.

Much has been written about the human and social impacts of the Mozambique LNG project, paused since 2021 under force majeure and expected to restart in the coming days. In addition to allegations of civilian killings by Mozambican security forces operating from the project site in Cabo Delgado, construction has involved the complete removal of several villages and denial of access to local people’s traditional fishing grounds.

But the marine environment may also be a major obstacle to further development. The Quirimbas Archipelago, where Mozambique LNG is located, contains more than 180 species of coral — the highest diversity documented outside the Coral Triangle. In June, a coalition of NGOs published True Risk, a report detailing the threats posed by further development to the uniquely biodiverse habitats that fringe the coasts of Cabo Delgado.

This isn’t just a problem for TotalEnergies’ Mozambique LNG project, but for the whole effort to extract gas from Mozambique’s offshore fields, including ExxonMobil’s sister project, Rovuma LNG. The oil and gas industry’s interlinked impacts on the human and natural environment are nothing new — the long history of Shell’s operations in Nigeria is another perfect example. But with advances in remote sensing data, we can now see what’s happening in near-real time.

Dredging in Palma Bay

To track recent offshore work at Mozambique LNG’s Palma Bay site, we turned to AIS data — ships’ safety transmissions, which reveal their location — and daily satellite imagery from Planet and ESA Sentinel-2.

Reviewing the AIS data quickly put paid to the idea that work on Mozambique LNG has been completely paused: in fact, the project’s primary marine contractor, the Dutch firm Van Oord, has been busy carrying out dredging in Palma Bay since October 2024. A short note in Van Oord’s latest annual report confirms that the company has been digging a trench for one of the pipelines running from the offshore Golfinho gas field to the coastal export terminal.

Dredging of this kind is highly destructive at the best of times, but particularly problematic in an area of such rich marine biodiversity. Recent satellite imagery shows the direct removal of areas of live coral and the generation of huge sediment plumes by dredgers operating in Palma Bay, threatening to smother marine organisms over a wide area. See our research note for more details.

Risks multiply

To understand the rationale behind dredging a pipeline trench through an area of live coral, we consulted various iterations of Mozambique LNG’s public Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), alongside communications between the project and its major public lenders. These were obtained via a freedom of information request to the Italian export credit agency, SACE, submitted by a partner organisation.

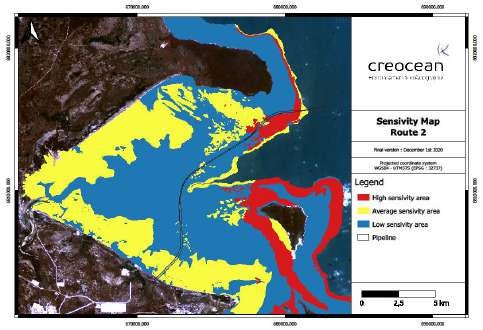

The documents present a clear but troubling picture. When the project was originally proposed by the US firm Anadarko, the plan was to build the gas pipelines along a relatively direct route from the offshore fields to the onshore processing plant. However, subsequent studies of the local marine environment — included as habitat maps in the documentation — revealed that Palma Bay is completely boxed in by areas qualifying as ‘critical habitat’, mostly coral reefs.

The dredging activity we’ve observed for the Golfinho pipeline follows a route that has been revised several times in an effort to minimise the impact on local ecosystems. But the photographic evidence is clear: even this circuitous route from the fields to the plant involves traversing — and therefore removing — areas of coral.

The next phase of gas development in Afungi, Rovuma LNG, involves building two more such pipelines, facilitating access to the Prosperidade and Mamba fields. At present, it is not clear if this development can happen without significant further destruction of local marine ecosystems.

Approached for comment on the apparent environmental impacts of the dredging, a spokesperson for Van Oord said: “The company carried out a number of preparatory dredging activities for TotalEnergies' Golfinho project in the second half of 2024 and the first half of 2025. These activities have now been completed.” TotalEnergies declined to provide an on-the-record comment.

Is it all worth it?

As Energy Flux’s Seb Kennedy lays out in an excellent piece on the commercial aspects of the project, TotalEnergies and the Mozambican state oil company, ENH, really have no choice but to continue with Mozambique LNG.

But although the project will generate tax revenue for the government and provide a limited volume of gas for domestic use, the compounding delays and disruptions driven by the security environment mean that it may be of little benefit to the people of Mozambique or the citizens of Global North countries whose governments’ coffers have backed the project.

Like many other proposed or under-construction export projects, Mozambique LNG is positioned to ship its first cargoes in the middle of an LNG supply glut the likes of which has never been seen. While the project remains profitable at current prices, a sustained downturn could mean that both its developers and the government fail to make a significant return.

In any case, Mozambique LNG will do next to nothing for European energy security, an oft-stated rationale for public investment in new LNG export projects. According to Kpler data, more than 120 cargoes have been loaded from the existing Coral South development since it started production in 2022, virtually all of them going to Asia. The number to Europe, including Turkey? Seven.