LNG unleashed isn’t working out as planned

The White House has made it a priority to fast-track new liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects, but escalating trade wars, energy security concerns and weakening demand mean not all is going to plan.

LNG lies at the core of White House ambitions to “unleash energy dominance” — a phrase that has come to define the Trump-era energy doctrine. In this worldview, fossil energy doesn’t just fuel the economy; it’s a tool of foreign policy, a geopolitical bargaining chip, and a cornerstone of Trump’s effort to rebalance trade on his terms.

Trump’s election appears to have been well received by those within the LNG industry who hoped to benefit from a rollback of climate legislation, de-regulation and expedited permitting. A blog post from Norwegian energy analytics firm Rystad summed the mood up predicting that Trump would “prime the liquefied natural gas (LNG) markets for a golden era” whilst his policies “strengthen the sentiment around LNG supply after years of uncertainty, helping to unleash long-term demand”.

Once in office, Trump’s LNG push got off to a flying start. On the first day of his second term, he signed an executive order repealing Joe Biden’s “pause” on new export licenses for LNG terminals. Four days later, Venture Global — one of America’s biggest LNG exporters — arranged one of the first major IPOs of Trump’s second term initially hoping to raise $110 billion.

The White House is now integrating the push for LNG in its fractious foreign policy and trade push. In April, Trump pressed EU officials to commit to buying more gas while his administration has also pushed Japan and South Korea to invest in ambitious new multi-billion dollar export projects. This is consistent with the White House’s commitment to reducing the trade deficit: an expansion of LNG exports can go some of the way. It also aligns with Trump’s desire to announce eye-catching deals with big numbers in telegenic settings. The push to get an agreement on the $44 billion Alaska LNG project, which wouldn’t come online until well into the 2030s, is emblematic of this approach.

While the ambition and effort is clear, this strategy appears to be running into major headwinds. Some of the early industry predictions of a “golden era” look premature as a more mixed and uncertain picture has emerged. Venture Global’s IPO flopped and shares have since cratered. Developers are struggling to lock in new long-term offtake agreements. One of the most strategic new export projects on the Pacific Coast — Saguaro Energía — appears to have been derailed by the fallout from the intensifying trade war with Mexico and China, while the latter country — the world’s largest importer of LNG — is pivoting away from U.S. LNG as it retaliates against tariffs with its own duties on imported U.S. energy.

Make no mistake about it, the United States is already the pre-eminent LNG power. It is currently the world’s largest exporter, and according to the Energy Information Agency (EIA) on track to double its export capacity by 2028, primarily through a massive build-out of export projects along the Gulf Coast. But work on most of these projects began during Joe Biden’s presidency, and the early signs are that — despite the rhetoric — many of the new administration's initiatives are undermining an industry that was previously on the up.

Atlantic realities

Currently, just over half of U.S. LNG traverses the Atlantic and ends up in homes, power plants and industrial facilities in Europe. The vast majority of these cargoes are sent from projects on the coasts of Louisiana and Texas. Volumes of LNG have gone up in recent years as Europe has weaned itself off Russian gas.

The $350 billion question

Energy analysts have been flummoxed by Trump’s recent suggestion that the EU should buy $350 billion of energy from the U.S. to reduce or eliminate the current trade deficit in goods with the EU. As several commentators have pointed out, the EU’s energy imports would have to increase by 500% to bridge the current deficit, and neither the U.S. nor Europe has the infrastructure to support the kind of uptick in LNG imports required.

While it does seem that the EU has some appetite to increase LNG purchases from the U.S., it’s not clear that purchasing more volumes from the U.S. will actually re-balance trade in goods with the U.S., nor will they deliver much-needed energy security.

Europe’s demand for LNG is falling in part because of its extraordinary efforts to drive down gas consumption. European LNG traders may be nervous about signing up to long-term agreements in the context of weakening demand. As Anne-Sophie Corbeau at Columbia’s Center on Global Energy Policy points out, if European companies did sign up to more long-term offtake agreements, and eventually sold more of their contracted volumes of LNG on to Asia as European demand weakened further, this would do nothing to impact the U.S.–EU trade in goods imbalance.

Then there is the question of energy security. The scars of over-reliance on Russian gas are still raw: does becoming even more dependent on an increasingly erratic trade partner make sense? The EU currently imports almost half of its LNG from the U.S., so any substantial ramp-up in volumes would turn a heavy dependency into a major strategic vulnerability.

Bear in mind that the U.S.’ reliability as an energy provider is not only being questioned by those (like the authors of this piece) who would like to see an urgent phase out of fossil fuels; oil bosses are also concerned. According to reporting by the Financial Times, TotalEnergies CEO Patrick Pouyanné, while supportive of closer ties with the U.S., says that Europe requires “some form of guarantee” of continued exports.

What has Pouyanné and others concerned is that U.S. LNG exports exert upward pressure on domestic U.S. gas prices. Higher gas prices will squeeze American consumers through their heating and power bills, and may also irk U.S. industries that require large amounts of gas, and have armies of lobbyists. What if American petrochemical companies, which rely heavily on natural gas, deploy their lobbyists in Washington, D.C. on the back of a natural gas price spike? Will Trump, already prone to a flip-flop, decide to curtail exports at the expense of those reliant on U.S. LNG?

There were already some concerns about the reliability of some U.S. LNG exporters prior to Trump. BP and Shell are currently pursuing the American gas exporter Venture Global for failing to deliver contracted cargoes, a situation which Pouyanné claims wisely to have avoided.

Leaky basins and methane rules

Another hurdle to more U.S. LNG imports is the EU’s Methane Rule. While initially requiring importers of gas to report on their emissions, this law should eventually penalise LNG importers whose upstream production exceeds “maximum methane intensity values”. U.S. diplomats and LNG firms are reportedly trying to hollow out the regulation before companies are compelled to report their methane intensity data.

Permian Basin LNG is notoriously methane intensive, so the EU’s new rules present a particular problem for U.S. LNG producers. Research by Cornell professor Robert Howarth has shown that gas sourced from the Permian and shipped to Europe or China can be worse for the climate than domestically sourced coal. While the conclusions have been questioned by recent reports published by industry consultants Wood Mackenzie and S&P Global, there has been no peer-reviewed response to Howarth’s conclusions.

Will EU policymakers be willing to backtrack on a cornerstone climate policy to appease a U.S. pushing more gas, or will they stick to their guns? If they do the latter, this could in the long run limit the amount of LNG that could be imported from the Permian Basin, which currently accounts for around a fifth of U.S. natural gas production and is adjacent to Gulf Coast LNG facilities.

Pacific dreams

While shipments to its traditional allies across the Atlantic still form the backbone of the U.S.’s LNG export programme, the future of the trade lies to the west. The fossil fuel industry has been exceptionally bullish on increased Asian demand: Shell estimates that 180 million more people will be connected to the gas grid in China and India in the next five years.

Organisations like IEEFA warn that forecasts like Shell’s may significantly overshoot, but analysts agree that demand from the three big east Asian LNG importers — China, Japan and South Korea — will make up a greater proportion of the global market in the coming decades.

Capes and canals

For U.S. exporters, this presents a geographical conundrum. Unlike exports to Europe, which face a relatively obstacle-free journey of 15 to 20 days to their destinations from liquefaction plants on the U.S. Gulf Coast and Eastern Seaboard, exports to Asia are far more constrained. Since the beginning of commercial U.S. LNG exports in the run-up to Trump’s first term, the preferred route to Asian markets has been westwards via the Panama Canal, with much longer eastbound shipments via the Suez Canal making up a smaller proportion.

Since the beginning of 2024, however, almost all U.S. LNG exports to Asia have avoided both canals, taking the much longer route — 50 days to China compared to Suez’s 46 and Panama’s 33 — via the Cape of Good Hope. The drivers are different in each case: in Panama, prolonged droughts have reduced the number of vessels that can transit the canal and pushed up prices for those that do, while regular drone attacks by Houthi militants in the Red Sea have scared western LNG shippers into avoiding the Suez Canal entirely. But the net effect is the same: to make the idea of a quicker route to Asia even more attractive.

The Mexican mirage

Step forward Saguaro Energía. The first of a planned wave of new export projects on Mexico’s west coast, this proposed 30 mtpa facility would sit at the top of the Gulf of California and liquefy gas piped southwards from the U.S. Permian Basin. This wizard wheeze would solve two problems facing the U.S. oil and gas industry: insurmountable opposition to new LNG export infrastructure in Democrat states like California, Oregon and Washington, and a huge surplus of associated gas — gas produced as a by-product of oil extraction — which has sent prices negative in the Permian.

But all is not going to plan. Having apparently ridden out the storm created by the Biden administration’s January 2024 pause on approvals for exports of LNG to non-Free Trade Agreement (FTA) countries, Saguaro Energía’s developer, Mexico Pacific, is facing an even more uncertain future under Trump. For one thing, the project is still waiting for approval of an extension to its original non-FTA export license, with no sign of movement. In February, 29 members of Congress wrote to Trump in deferential terms, begging the president to issue the license:

This will create thousands of jobs and solidify America’s position as a dominant player in the global energy market. We greatly appreciate your attention to this critical matter and your efforts to Make America Great Again!

But these regulatory troubles may be the least of Mexico Pacific’s problems. According to a recent Reuters report, the company has been seeking to renegotiate sales and purchase agreements (SPAs) with Chinese buyers due to rising costs demanded by its engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) contractor, Bechtel.

These cost pressures appear to be having immediate effects: a quick look at LinkedIn shows that Mexico Pacific has lost 30% of its staff in the past six months, including senior vice presidents responsible for business development, treasury and government affairs. The exodus culminated on April 16, with the announcement that the company’s CEO, Sarah Bairstow, would take up a new position with Australian LNG giant Woodside. As of mid-April, the project’s future remains highly uncertain, with U.S. Department of Energy filings suggesting that its owner — the private equity firm Quantum Energy Partners — may be in the process of selling up.

As Bairstow herself noted in September last year, the question of whether LNG exported from Saguaro Energía is considered Mexican or American for tariff purposes would be determined individually by importing countries. Even if we assume that it is considered of Mexican origin by all importers, risks remain, not least from Trump’s own strained diplomatic relations with Mexico and the effects of his 25% tariffs on steel, a crucial component of any LNG facility and its connecting pipelines, and potentially a major driver of the cost increases being demanded by Bechtel and other EPC contractors.

China’s LNG cards

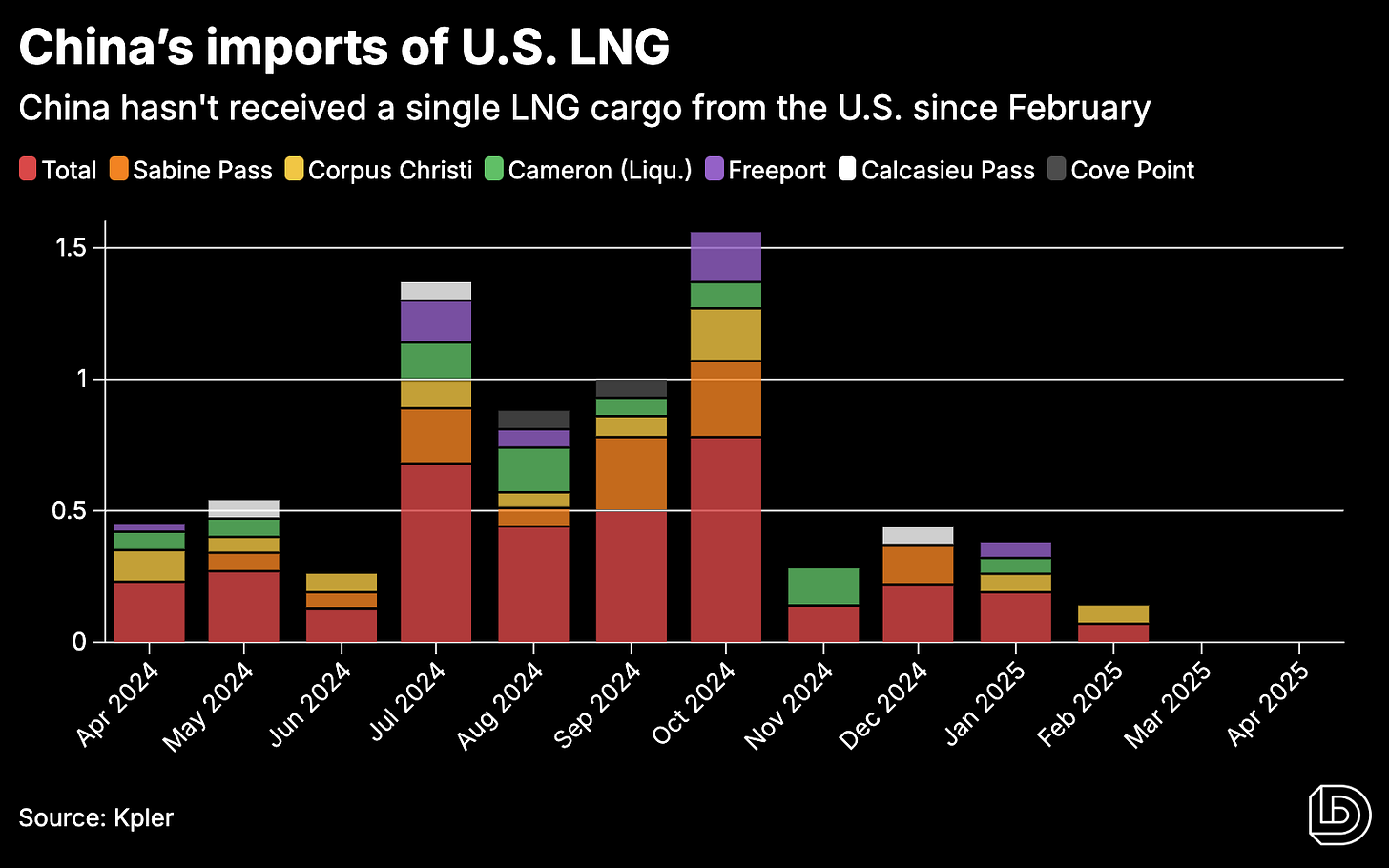

Under Trump 2.0, the fossil fuel industry has been lavished with praise, but actions — particularly when they affect international trade — speak louder than words. In response to the U.S. president’s initial 10% tariffs on goods coming in from China, Beijing whacked a 15% duty on LNG imports from the U.S. The fallout from ‘Liberation Day’ means that Chinese tariffs on U.S. goods, including LNG, now stand at 125%. As a result, China has stopped importing U.S. LNG entirely, diverting all its contracted cargoes due to arrive in March and April to third countries, mostly in Europe.

Robust Chinese demand for LNG is key to new Pacific projects. Mexico Pacific itself has sales and purchase agreements in place with two Chinese buyers — Zhejiang Energy and Guangzhou Development Group. But if trade tensions don’t ease, then China may stop signing offtake agreements for new U.S. projects, making it harder to raise the immense capital required to build new export terminals.

The challenge for the U.S. is that it has relatively little leverage with China when it comes to LNG. Based on 2013 averages, U.S. imports make up just 6% of China’s LNG slate, but China itself makes up 10% of demand for U.S. LNG. In other words, a halt to Chinese imports will hurt U.S. companies more than it would Chinese ones. China may turn increasingly to Russia, which as we discuss below is warming up its beleaguered Arctic LNG 2 project, which can deliver cargoes via the Northern Sea Route. At the end of 2024, Beijing and Moscow also completed a 3,175 mile pipeline called the Power of Siberia which can deliver Siberian gas to China via Kazakhstan.

Arctic ambitions

Writing about Greenland in the latest LRB, James Meek notes that Trump has an affinity for the north, hypothesising a family connection: his mother hailed from the Outer Hebrides, while his paternal grandfather ran hotels in northern Canada. Whatever the reason, Trump’s fascination with the potential of Alaskan energy resources fits squarely into this mould, and sets up another potential route for U.S. LNG across the Pacific.

Among the flurry of executive orders signed on the president’s first day in office was one on ‘Unleashing Alaska’s extraordinary resource potential’, at the centre of which is a promise to “prioritize the development of Alaska’s LNG potential, including the permitting of all necessary pipeline and export infrastructure related to the Alaska LNG Project”, a $44 billion project that envisions piping natural gas over 800 miles from the North Slope to a liquefaction plant in southern Alaska. As with the Mexican option, its key selling point is geography, and the relatively quick route it would provide for shipments to Asia.

Alaska LNG faces hurdles that even presidential enthusiasm will struggle to overcome, notably the sheer cost, engineering complexity and likely environmental opposition. Despite these, and similarly to how increased LNG sales are being used as a bargaining chip in trade negotiations with the EU, Alaska LNG has become central to the U.S.’s negotiations with South Korea. The two countries reportedly discussed the project directly in recent days, while Japanese conglomerate Mitsubishi is also reportedly considering investing in Alaska LNG.

Even under the most optimistic scenario, LNG won’t be steaming out of Alaskan waters until the 2030s. In the meantime, the wild card in the north is Russia’s Arctic LNG 2 project, to which we’re no strangers. Following a wave of investigations in 2023 detailing how U.S. and European engineering companies were helping the Russian firm Novatek complete this highly strategic LNG export project, the Biden administration applied several packages of secondary sanctions, stalling construction and meaning that any companies trading its cargoes risked severe legal repercussions.

According to trade data from Kpler, every cargo shipped from Arctic LNG 2 so far has ended up in Russian floating storage due to a lack of willing buyers, leading the plant to effectively shut down last autumn. But with talk of a potential rapprochement between the U.S. and Russia, the future of the project looks brighter. A recent paper from the Oxford Institute of Energy Studies models the potential effects on the European gas market of sanctions being lifted, while flaring activity observed via satellite imagery suggests that the project may be restarting production.

From the perspective of the commodity markets, increased Russian LNG exports mean lower prices and more competition for U.S. sellers — hardly a geo-strategic win. But under Trump 2.0, things are not always as they seem. In a future in which the global trade in fossil fuels is increasingly contested, with different blocs putting forward different visions of the future energy system, the shared interests of producer countries in maintaining global demand may be more important than their commercial differences.

In other words, while the U.S. may not be looking to join the the Gas Exporting Countries Forum (GECF) — the ‘gas OPEC’ — any time soon, its broader interests as an exporter to the EU and Asia put it in alignment with countries like Russia and Qatar.

In a disordered world, fossil fuels ramp up risk

A single journey by a large container ship filled with solar PV modules can provide the means to generate the same amount of electricity as the natural gas from more than 50 large LNG tankers or the coal from more than 100 large bulk ships.

International Energy Agency (IEA), Energy Technology Perspectives, 2024

As global trade and finance convulses, and the world’s most powerful country ups the ante with its particular brand of fossil fuel diplomacy, there is a real risk that major LNG importers are cowed into financing the next round of LNG expansion beyond the massive increase in capacity already slated this decade. This should be resisted.

While economic inter-dependence can help sustain peaceful relations, the fundamentals of hydrocarbons create unhealthy dependencies and severe vulnerabilities for all those that remain dependent on them. LNG is no different. The constant need to restock volatile fuel that needs to travel thousands of miles across seas invites the possibility that an unreliable exporter may choose to divert those supplies for financial or political gain, threatening blackouts and misery. All this, whilst saying nothing about the existential threat that the continued burning of them creates for our world.

It could, and indeed, it has been argued, that the renewable transition will create the same material dependencies, most notably on China given its dominance of battery manufacturing and the processing of some of the metals like lithium and cobalt that underpin renewable power systems. While this is true, the dependency is naturally weaker. Metals can be recycled, and as this pertinent observation by the IEA encapsulates, there is simply much more potential in a container ship of solar panels than there is in a single tanker of LNG. One is the tool to unleash near unlimited, cheap energy for decades to come — the other is a commodity that will likely be burned within a few months, stored in the atmosphere for a centuries as CO2, and require near immediate replacement.

As politicians and civil servants across Europe and Asia grapple with the latest convulsions of global trade — and feel the heat to finance more LNG expansion — they'd do well to remember this fundamental truth.