Cowpats in your coffee?

Biogas isn't a silver bullet — and it probably isn't vegan either

King’s Cross Central (KXC) — a big development of flats, shops and offices north of London’s King’s Cross and St Pancras railway stations — is built on gas.

In one sense, this is literally true: several of the buildings occupy old gas holders or ‘gasometers’, those big, hollow cylinder structures that you see all over British towns and cities, which used to hold coal gas. Even today, though, the development relies heavily on natural gas for its electricity and heat generation, as KXC’s latest sustainability report makes clear.

KXC uses gas to power a big combined heat and power (CHP) plant, generating electricity and providing central heating for buildings at the same time. About 50% of the generated electricity is fed back into the grid, while buildings offset some of their consumption with on-site solar panels. Under a power purchase agreement between KXC and an English solar farm, the developers contribute to decarbonising the UK grid, while any electricity pulled from the grid comes from certified renewable tariffs.

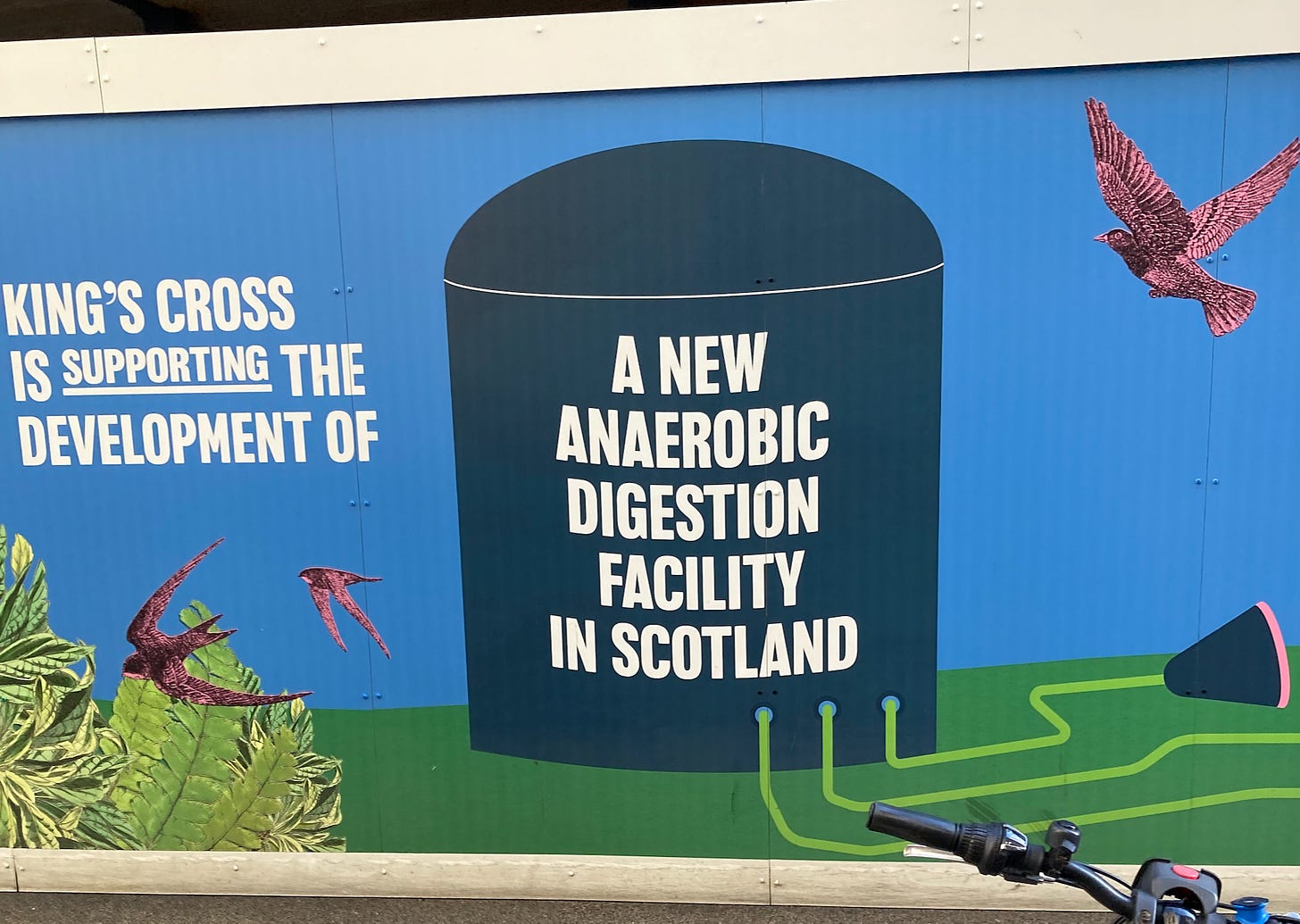

KXC’s developers are proud of these green credentials. Along the new King’s Boulevard, a set of hoardings that during the pandemic exhorted citizens to “SHOP EAT DRINK [EXPLORE/RELAX/PLAY/DISCOVER]” have been replaced with signs about carbon offsetting and net zero.

One claim piqued my interest enough to investigate further. According to the signs, KXC is “supporting the development of a new anaerobic digestion facility in Scotland”. Anaerobic digesters (ADs) capture biogas from the decomposition of material like food waste and animal manure, and in some cases ‘methanise’ it, creating a fuel which can be used in place of natural gas.

Some quick Googling revealed that the digester in question is a project near Dumfries, Scotland. According to a 2021 press release, KXC has signed a deal to buy 100% of the gas generated at the facility, meaning that “all the heating and hot water for the [King’s Cross] estate’s 2,000 homes, 4 million square ft of offices, retail and dining space will be powered by green gas” — this latter term being repeated throughout the website.

You might be forgiven for thinking this means gas from Dumfries will be physically transported to central London — this is certainly the way the deal is presented in the press release, which talks about “40,000MWh of green gas delivered to King’s Cross per annum from an Iona Capital owned plant.” In reality, the arrangement uses a “virtual green gas supply agreement”. The digester injects gas into the grid; KXC pulls the same amount of gas out of pipes in London, where it is much more likely to come from underneath the North Sea or an LNG tanker from Qatar.

So how does this digester generate its gas, and what exactly makes it ‘green’? According to one of the project’s investors, most of the digester’s feedstock “comes from […] a large dairy farm, and the neighbouring farm, […] which is a large beef farm.” In other words, biogas is generated by pumping cow shit into a big pit known as a ‘lagoon’ and covering it with an airtight seal. As the aerial imagery above makes clear, this isn’t a small operation, and it’s by no means the only one in the area — the Biogas Map published by NNFCC, a biogas consulting firm, shows approved (blue) and operational (green) ADs across south-west Scotland.

The climate logic is simple: by covering liquid manure that would otherwise be open to the air, AD developers capture methane — an extremely potent short-term greenhouse gas (GHG) — that would otherwise have escaped into the atmosphere. Even if this biogas is then burned as fuel, the process of combustion converts it into CO₂, which is a less damaging GHG, and some quantity of emissions is therefore avoided. Every megawatt hour of biomethane produced also displaces a megawatt hour of fossil gas from the grid. The specifics will be worked out in detailed documentation by the project developers and assessors from the Green Gas Certification Scheme.

This is all well and good as far as it goes. Of course we should capture methane that might otherwise be vented into the atmosphere. There are risks: if you’re collecting and storing large quantities of an extremely potent GHG, you better make sure it doesn’t escape, something that seems to happen disconcertingly regularly. But even without technical hiccups, the dash for biogas interacts with other questions that we need to consider if we want to move to a fully decarbonised economy. Questions like: should we really keep consuming all this beef and milk in the first place?

It seems that not all the manure at these farms ends up in the digester — in the photograph above, an open slurry lagoon is clearly visible on the left. And a quick search of planning applications filed with Dumfries & Galloway council shows 179 matching this delightful term, with significant spikes in applications since 2018. There may be any number of confounding factors here — changes to planning requirements, evolving terminology, limited digitisation of historic applications — but it seems clear, at least, that a large number of lagoons is still being built in the area.

For farmers, technology to mitigate methane leaks — the development of which is often supported by grants from central and local government — offers a new revenue stream. By capturing something that was previously considered waste and putting a price on it (a very high one given the recent history of the European gas market), we are, as a society, making livestock farming — a practice responsible for more than 14% of anthropogenic emissions — more profitable. And not just any type of farming: the economics of ADs only really works at agro-industrial scale.

Your average Farming Today listener might not think that’s a problem — and maybe you don’t either. But next time I’m warming up at Caravan with an oat milk latte, I might stop to consider the whether it’s really as vegan as I’d assumed.