A contrarian take on disposable vapes

Is wasted lithium a problem, or might it encourage the investment we need for a speedy transition?

Unless you've been living under a rock for the past few years, you'll have noticed the meteoric rise of disposable vapes. The most popular brand in the UK is the Elf Bar, a stick-shaped device that delivers 600 puffs of nicotine-infused vapour, powered by a small lithium-ion (Li-ion) battery. I’ve tried them myself, though couldn’t get on with the flavours, and have three or four sitting in a drawer at home.

The ‘disposable’ part has got people pretty exercised, especially if they’re familiar with the narrative that positions lithium as the new oil — the crucial commodity for production of batteries for electric vehicles, and an element which a simple view of price signals suggests is in short supply.

I’d already watched a few YouTube videos about scavenging and recharging the batteries from disposable vapes — then this tweet from Hazel Southwell went semi-viral within my Twitter niche last week:

Southwell’s main issue — as set out in an really interesting post on her newsletter — is the potential for discarded lithium cells to start fires, which is pretty concerning. She also acknowledges that a lot of the costs involved in producing batteries bear little relation to raw materials: over the pandemic, soaring freight rates and a shortage of semiconductors have arguably had a greater impact.

But something has always bugged me about the underlying point — that disposable vapes are a ‘waste’ of lithium. Do their tiny batteries really represent anything more than a rounding error in global demand? And even if they do, does this zero-sum model — vapes are taking lithium from electric vehicles (EVs) — stack up?

On one level, yes, it clearly does. Lithium is a finite resource: there is only so much of it in the ground. By sending Li-ion cells to landfill, we might not be destroying the materials they contain forever, but we’re making it seriously difficult to recover them. But instead of going all Gollum over a few bits of metal with some salty water inside, let’s consider what we actually need lithium to do for us as a species over the next few decades, and how best to make that happen.

The key promise of lithium-ion batteries is that they will provide a cheap and reliable way to almost completely decarbonise road passenger transport — a climate win if ever there was one. There is already a large sector of battery tech R&D focussed on alternative chemistries like sodium-ion, with the specific aim of developing technology that we can use when total supplies of extractable lithium finally decline, likely towards the end of this century. The real value of lithium-ion, as Simon Moores testifies on the latest episode of the Redefining Energy podcast, is that it’s what we have now — in a scenario where rapid decarbonisation is an existential imperative, it makes sense to go hell-for-leather to get it out of the ground and into engines.

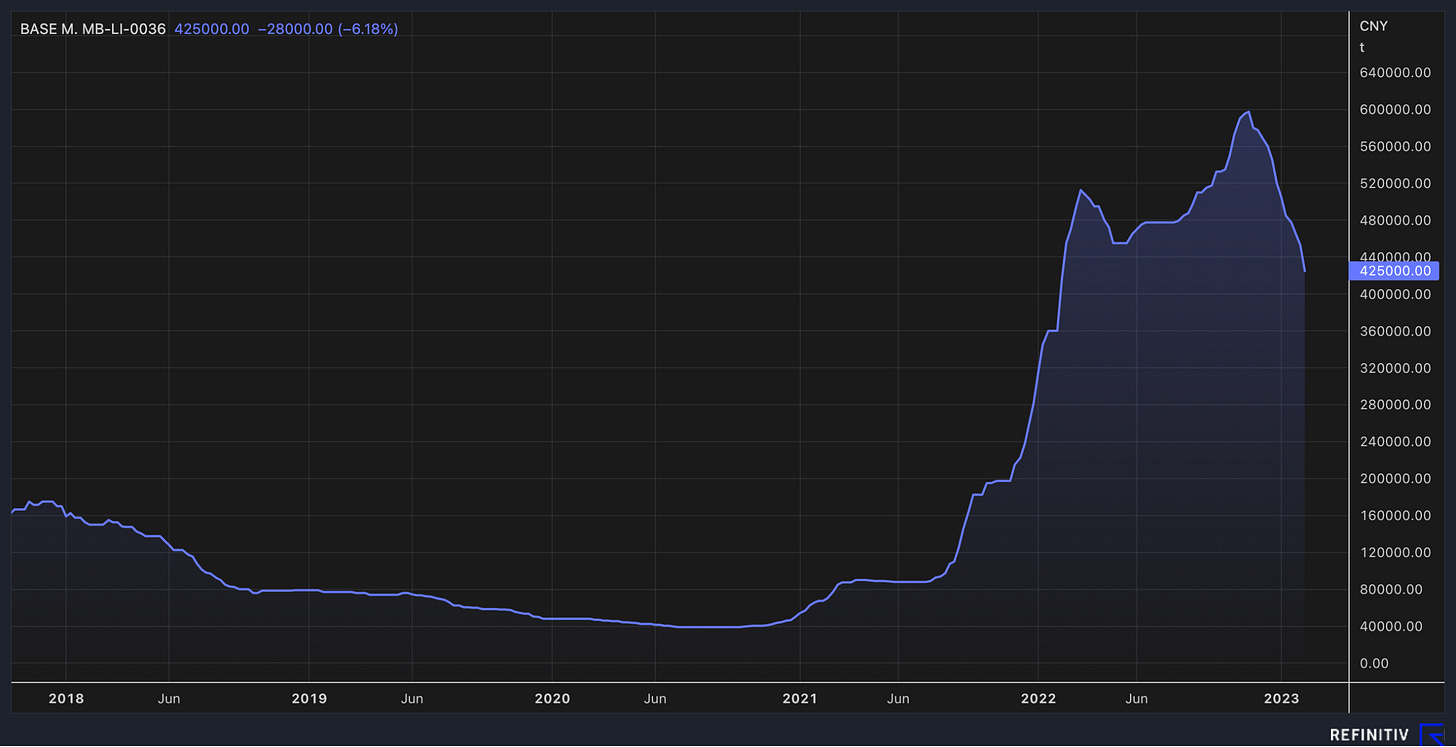

In the meantime, as with any commodity, lithium’s price is driven not by its total reserves, but by the balance between current demand and supply. One way to think about this problem is that we can increase the supply of lithium for EVs — and decrease its price — by banning disposable vapes. But this leaves supply levels static: the same amount of lithium is being produced each year, when we need huge increases year-on-year to meet current decarbonisation goals. The more salient problem is investment, which is driven by demand.

Demand for large and expensive consumer durables tends to be choppy — people buy in the good times but can’t afford to buy when times are tough. So far, the trend in global EV adoption has been hugely positive, but as any good investment manager knows, “past performance is not indicative of future results” — and a significant downturn, even if temporary, could seriously damage investment in the supply chains needed for affordable production of lithium in the first place.

As we’ve all learned over the past few years, supply chains work well in environments that are stable and consistent — and it’s difficult to think of a more consistent consumer than the humble vape fiend, buying a couple of vapes a week, rain or shine. In conjunction with our incessant turnover of consumer electronics, many of which now also use Li-ion cells, I can only assume that Elf Bars are playing their (admittedly small) part in creating the economic incentives needed for more investment in lithium production worldwide.

So what are the actual numbers on waste? Sticking to the UK, where the issue was seriously considered in a joint investigation by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, Sky News and the Telegraph last summer, the figure is two vapes containing 0.15g of lithium each thrown away per second, “enough lithium to make roughly 1200 electric car batteries” over the course of a year. This is a bit like saying that the amount of aluminium thrown away as Coke cans each year is enough to make… 100,000 bike frames. It might (?) be true, but it’s only a problem if there is consistent demand for aluminium bike frames and the constraining factor is supply of raw materials, not capital investment, labour costs or energy costs.

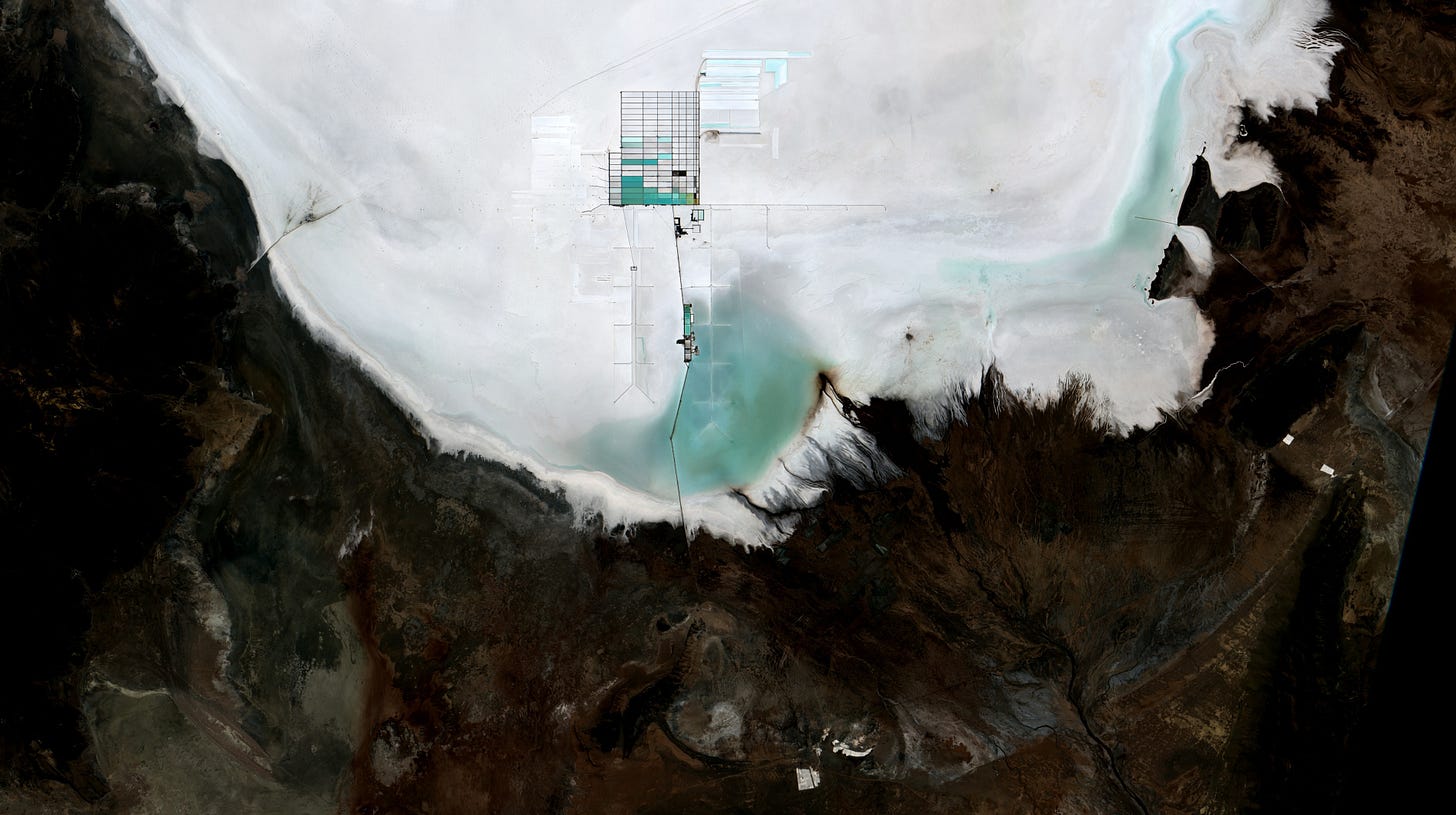

There is valid precedent for treating commodities as scarce resources for which different use cases compete — criticism of the United States’s policy of blending 10% corn-derived ethanol into the petrol supply has relied on this logic, arguing that the crop would be better used as food. In that case, though, the real limiting factor is land. Lithium mines carry all the risks and harms inherent in any large extractive project, but they are at least geographically dispersed, and, with investment, can benefit from using modern technology. The massive evaporation ponds used at current lithium mines consume a lot of water — but as Hannah Ritchie recently pointed out, the overall extractive footprint for ‘transition minerals’ will be tiny when compared to the fossil fuel industry.

All this is probably enough to make Jason Hickel — whose book Less is More I found genuinely compelling, if provocative — puke. Clearly the most important driver of investment in renewable energy and the production of the minerals that power it is public policy like the US Inflation Reduction Act, which provides economic and political incentives over and above those offered by rising demand. And I’m not taking into account any of the other effects that disposable vapes have in the world — I think those are probably a net positive in terms of adult health outcomes, but their popularity among The Kids is worrying, and could lead to sudden demand shocks if governments follow Australia’s example in cracking down on the sector.

Sometimes it’s important to resist a conservationist reflex, though, particularly when there are other factors, like the speed of collective action and the future development of technology, to factor in. Considered as one of a number of variously useful products that we make with lithium, I don’t think vapes should give us too much cause for concern. The proof, as ever, is in the price: two for £10 at my local corner shop.